And then – there was nothing. This is the kind of show that requires a large fit up crew and then perhaps two – maybe three – people to run it. As it turned out, we had an entire first year crew to find jobs for; a task we tried so hard to be good at. Every job we found was given to a crew member, however small it was, and I resorted to teaching knots classes out of a necessity to kill time. To be in a Deputy or Acting HOD position and see your crew get bored in front of you is quite a disheartening experience – not least because you feel they’re not achieving the learning experience you know you should be helping to provide them. I don’t know what the solution to this is yet – though if a similar thing were to happen in future, I feel my approach of constantly offering my time to teach and answer any question I can would be a useful one, as it would allow those with an interest to attain any extra knowledge I could give them, and make some better use of otherwise lengthy down time.

Testing How Fire Retardent our Blacks Were

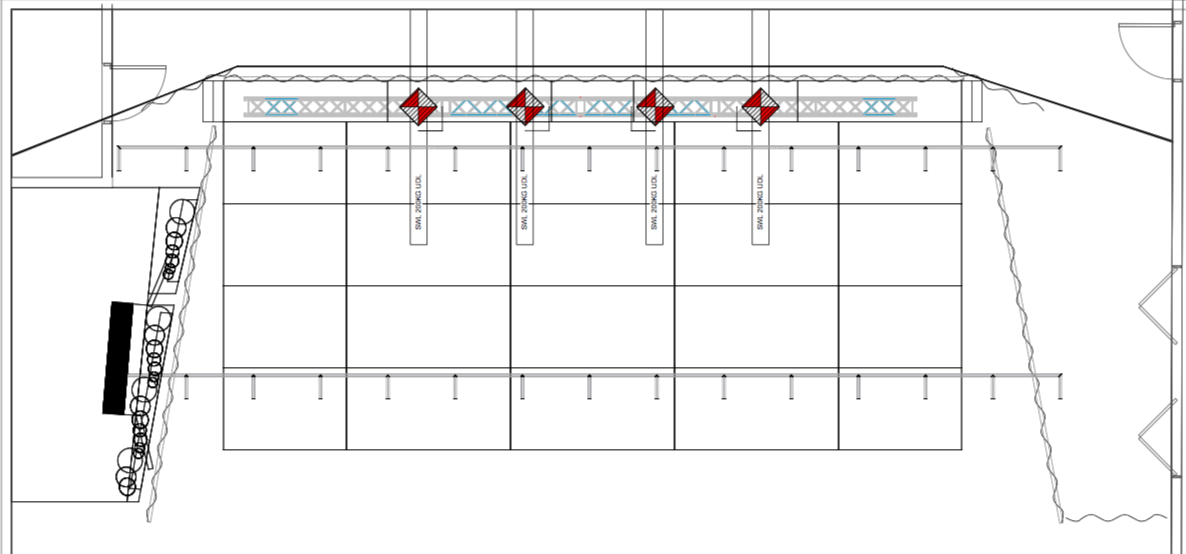

Our one moment of excitement in the process came in the form of a broken chain motor. Between one pyro reset and the next, Chain Motor four on the back truss jammed, meaning we could not lower or raise the truss at all. This, at first, did not seem that urgent an issue, as the TSM was happy to dead the truss till the strike and rig an extra bar for pyro to be rigged onto, which could be flown in and out between performances. However, the lighting designer was unhappy with this fix, as he pointed out that the units on that truss were known to fail, and – should this happen – we had no safe way of switching them out. Whilst I held down fort in the venue, Reece, Steve, and Kev set about trying to locate another of the same type and speed of motor which we could replace out in order to solve our issue. Eventually, one was found, and with Malki’s help, was switched with the broken one, thereby meaning that the truss was fully operational once again. This demonstrated two things to me. One – that the Scottish theatre industry is small enough that Steve and Kev could both end up contacting the same person with the same request within half an hour of each other. And two – that no matter how well you think a project is going, there will always be something that throws you off balance. In the sessions that followed, I chatted with Reece about other ways we could have fixed the problem. My suggestion was that we stagger the truss in between the three remaining 1/4Ts and a 1/2T from stock, and then re-rig in such a way that the two outside points hung from 1/4Ts and we created a centre point, bridled from the beams, and hanging on a 1/2T. This idea clearly had issues – it didn’t solve the problem of different motor speeds at all, and the additional calculations would mean it wouldn’t have been a fast fix – but it was nice to be able to work through my ideas with someone, as it challenged me to justify and find issues with my own ideas, rather than assuming them to be flawless.

Blacks Go Up (and Down and Up and Down)

After five performances – and a shortened performance rehearsal session which saw one of the MDs question why the show was being cut to suit ‘the tech people’ – we started the strike. As this followed the final performance, it had an energy about it often missing from RCS strikes; the crew well aware that the sooner we finished, the sooner we got to leave. The back black was the first thing to come in, as we were stowing it on the ground for Grant and Blacklight crew to re-rig the following Monday. Because of this, we de-rigged the steels and sent only the lines back up with sand bags on them, as it would be easier to just raise the bar on hemp and not worry about the harnessing required to dead hang it as before. The side tabs came down next and were completely struck, followed by all hard masking, and finally the deck at the back. After the catwalks were hoovered and the stage swept, all equipment was returned to the dock and the venue left as ‘spotless’ as it was when we found it. We left the Stevenson Hall at six o’clock – two hours after the performance had come down.

Raising it to the Ground

In conclusion, this year’s Christmas at the Conservatoire taught me two major things. It taught me the importance of planning – not just before a project begins, but at every stage, and the necessity to always formulate solutions to problems which haven’t occurred yet; because at one point they will. The second thing it taught me, was how to manage a crew. Reece deliberately took a hands-off approach to his role on this show, allowing me the chance to coordinate the crew and what they were doing. This was a great environment to learn these skills in, as I felt like I was actively learning how to be an HOD and how to put those skills into practice, whilst not having the fear of being on my own without someone there to support me – something I am very grateful to him for. Overall, this allocation is always a good one to round out the year with, and made me look forward even more to a Christmas and New Year’s rest.

SaveSave